I’ve been on a bit of run of alternating between sea shanties for my playlist posts and historical books for my recommendations. So it feels like a good time to split the difference and post a historical book about pirates.

In a way, the General History of the Pyrates — full title: — A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates — delivers exactly what it promises.

[And, uh, FYI: “Pyrates” isn’t a typo, at least not on my end. Spelling conventions change over time, and “pyrate” was an acceptable form of the word circa the early 1700s.]

On the other hand, that very History is, well, kinda dodgy.

Quoth Wikipedia:

is the only one that doesn’t cite a source…

From the Wikipedia article about Anne Bonny.

Now, that doesn’t mean the General History has no value, and it is a very interesting read, even if/though/when it’s not a credible historical account.

To paraphrase Pop Culture icon — for any number of reasons — Leonard Nimoy: The following tales of piratical exploits are true. And by true, I mean false. It’s all lies. But they’re entertaining lies.

And in the end, isn’t that the real truth?

For what it’s worth, that wouldn’t matter quite so much when the book was first published back in 1724.

So I can only assume the whole century was exactly 100 years of exactly this.

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels.com

If you’ve spent any amount of time studying History, you will almost certainly have realised that both the literary form of written histories and what the authors understood their role as writers of histories to be have changed across time and place.

In general, present-day History is written to be detached, dispassionate, and fundamentally true, and it’s usually understood that a written account that isn’t any or all of those things fundamentally isn’t History.

Not, of course, that this stops crackpots from trying to pass off completely nonsensical theories as fact. I’m not going to name names, but I’m sure something leaps to mind reading that line.

And even a perfectly credible historian claiming to be detached, dispassionate, and scholarly will inevitably have certain inherent biases…

At other points in time, however, authors understood the role of History and the duty of the historian differently. Ancient histories tend to have a moralising aspect that modern history tends to avoid — things like “We lost at Cannae because the consuls neglected traditional Roman values“, “Liu Bei was the legitimate successor of the Han Dynasty“, or “the British Empire is great because we have a moral obligation to civilise the barbarians.”

And then, of course, there are Histories written largely to be deliberately scandalous, salacious, or to satirise important people — something that dates at least as far back as the Romans: the Historia Augusta is infamously unreliable and describes some things not to be spoken of in polite company, while Procopius‘ Secret History and Buildings seem to be intended to subtly make fun of Justinian and his reign.

Photo by Arefin Shamsul on Pexels.com

And that’s basically what we’re getting into with the General History of the Pyrates. Of course, the reality is less glamourous than the popular notions, but then as now, pirates were larger than life characters, rebelling against corrupt political authority, doing cool things and getting stupendously rich and famous doing them. Pirates have always been prone to exaggeration and romanticising.

The author of the General History — whom we’ll get into in more detail soon — knows exactly what the good burghers of 1720s England expect in a book about pirates: larger than life characters, with their exploits relayed in salacious detail. But not too salacious. The book is literally prefaced with a disclaimer how the book is intended to allow honest sailors to recognise what pirates do so they can avoid doing it themselves.

The author of the General History identifies himself as “Captain Charles Johnson“, a name almost universally thought to be a pseudonym. Notably, there was a different Charles Johnson who wrote a play about the pirate Henry Every.

A longstanding, but also heavily-criticised, theory suggests that he was actually Daniel Dafoe (not to be confused with Willem). That name should sound familiar due to being the author of Robinson Crusoe. The other main contender for Captain Johnson’s secret identity is the printer and journalist Nathaniel Mist, or at least somebody commissioned by Mist.

While adding “Captain” to your name is a great way to seem more credible as an authority about pirates, Captain Johnson, whoever he actually was, seems to familiar with life at sea to, so there’s a decent chance he was actually some kind of professional sailor. Notably, Nathaniel Mist was a sailor who spent time in the West Indies — a potential point in his favour, perhaps, but hardly conclusive.

If anything, the longstanding mystery just adds another layer of compellingly scandalous material to gossip about.

And I feel like the good Captain Johnson, whoever he was, wouldn’t have it any other way.

Original footage from Canal+, image via giphy.

via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

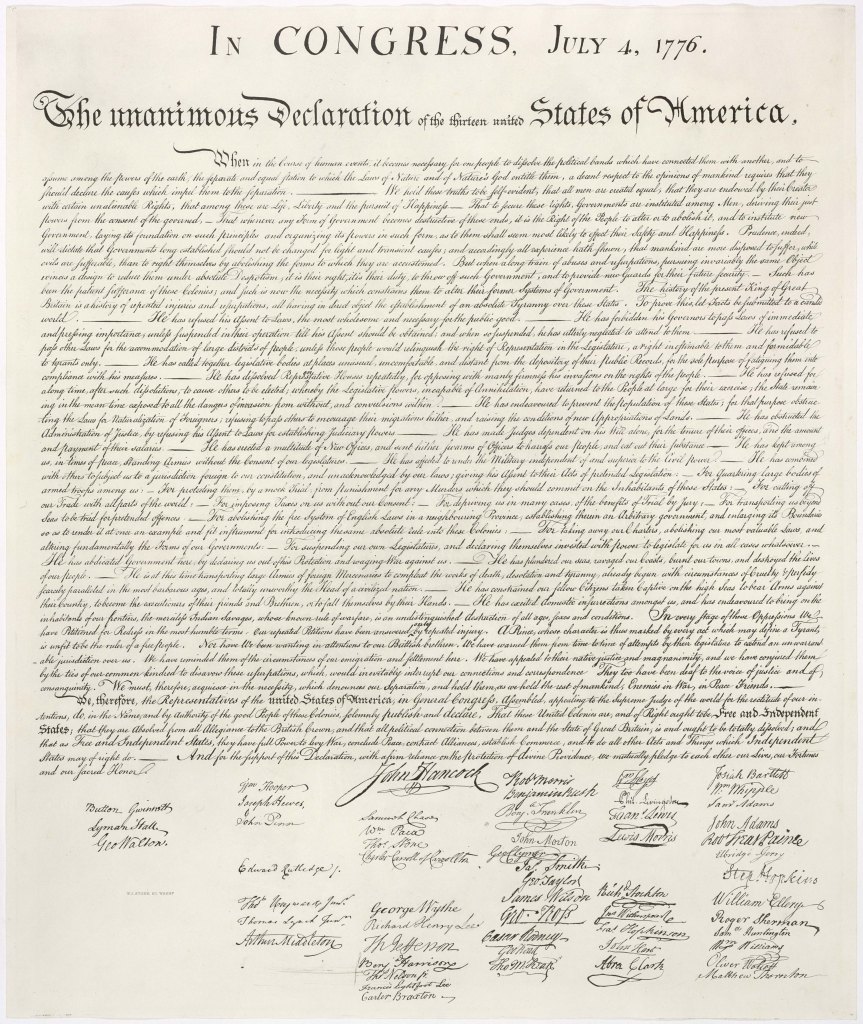

There’s a great line in National Treasure where Nicolas Cage reads a passage for the Declaration of Independence — a 44 word sentence providing the basic rationale for the Revolution — and concludes that “people don’t talk that way anymore.”

And it’s true. The prose of the 18th century is generally a lot more verbose than the prose of the 21st. And well, yeah, people seem to have gotten better at getting to the point in the intervening centuries, there’s just something about the 1700s literary style that just sounds so cool.

And for me personally, that’s a big part of enjoying the General History. It recalls me to the Elder Days of the War of Wrath Third Year of my Humanities undergrad, which was probably my favourite of the four years (Second Year was too hard, First Year wasn’t hard enough, and Fourth Year inflicted Hegel upon us) and dealt with the same time period as the General History and a lot of things with a very similar writing style.

A crop of Washington Crossing the Delaware: Emanuel Leutze.

Image via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Also, incidentally, when I learned that prominent Elizabethan courtier and intellectual Sir Philip Sidney was fatally shot in the leg after chivalrously refusing to wear leg armor into battle…

And now we sort of circle back to the “entertaining lies” thing: A General History of the Pyrates doesn’t necessarily have as much value as it perhaps could or should as a historical text, but I feel like it has an undeniable historiographical value.

At the very least, you’re going to learn at least the names of more than a few actual historically notable pirates, and at least the broad sketches of their lives, even though most of the details have been exaggerated and stylised, if not invented entirely.

And because of that, this is basically where we can trace the origin of a lot of the common knowledge about pirates in general and the versions of several famous individual pirates that exist in the popular consciousness.

Now, a quick reminder that I am a professional writer and editor, and if you’re in need of writing and editing support, please consider taking a look at the work and rates currently offered by Emona Literary Services™ and reach out if you think I can help you.

Please consider supporting Emona Literary Services™ to help me expanding my publishing and content creation projects, via Patreon, Ko-fi, or directly through Paypal by scanning the QR code below:

You can follow me on my various social media platforms here:

© Joel Balkovec — Published by Emona Literary Services™.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The author prohibits the use of content published on this website for the purposes of training Artificial Intelligence technologies, including but not limited to Large Language Models, without express written permission.

All stories published on this website are works of fiction. Characters are products of the author’s imagination and do not represent any individual, living or dead.

View the Emona Literary Services™ Privacy Policy here.

Leave a comment